✨ Health insurance, now in PayFit - learn more

💷 All the rates & thresholds you need to know for 25/26...right here

✨ The Payroll Journey: Start, Scale & Succeed Globally - learn more

✨ Health insurance, now in PayFit - learn more

💷 All the rates & thresholds you need to know for 25/26...right here

✨ The Payroll Journey: Start, Scale & Succeed Globally - learn more

Holiday pay mistakes can very easily turn into a costly headache for employers.

Fail to properly account for overtime, commission and allowance payments in your calculations, and you may suddenly be faced with an expensive series of back payments you need to make to rectify these underpayments.

This month, the Supreme Court published a highly anticipated judgement in the case of Chief Constable of Police Service of Northern Ireland v Agnew. In it, they overturned the three-month break rule which has previously hampered holiday pay claims since 2014.

The decision is one of the latest in a long string of critical holiday pay cases which may see some employers having to backtrack and rethink how they calculate holiday pay.

Let’s hone in on the key findings of the Supreme court’s ruling on holiday pay and look at some practical takeaways you can extract and action as an employer.

The case involved over 3,300 police officers and 350 civilian employees bringing claims against the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI).

This group argued that PSNI had unlawfully deducted wages from their holiday pay, resulting in underpayments that, for some, dated back years. PSNI had based the claimants’ holiday pay solely on their basic salaries, without including additional elements of pay in their calculations. These additional elements included things like paid overtime.

The act of including regular overtime and specific allowances in holiday payments is nothing new, and has already been established as a more compliant practice by previous legal cases across the UK and EU. PSNI was fully accepting of this and the Supreme Court's ruling on this holiday pay matter. What PSNI did dispute, however, was how far back these claims could go.

They made several arguments to this effect, but perhaps the most relevant for other employers was in relation to the definition of a ‘series’, where the claims were based on a series of underpayments. PSNI argued that where a series of lawful and/or unlawful deductions were interrupted by a break of three months of more, that the ‘series’ wasn’t legitimate.

For those familiar with the two-year backstop used in Great Britain which limits unlawful deduction claims, this did not come into question during this case. The decision only applied to Northern Ireland and its jurisdictions.

The Supreme Court made several crucial findings, specifically to do with the definition of a ‘series’ within the context of unlawful wage deductions. Upholding the previous decision of the Northern Ireland Court of Appeal (NICA), it was decided that:

A gap of three or more months between deductions does not automatically constitute a break in the series or cancel out the series. Back in 2014, Bear Scotland Limited v Fulton originally established this ‘three-month break rule’. The Supreme Court’s decision in this current case basically overturns this previous ruling.

A series of deductions shouldn’t necessarily be broken, even when a lawful payment is made in the midst of the series - that will depend on the specific circumstances in that case.

Whether or not a deduction forms part of a series is a question of fact in each case. In other words, it will be up to a tribunal to consider all relevant circumstances - frequency, size, impact - in deciding whether or not a series exists and whether there's a common ‘fault’ linking these underpayments.

Payroll audit guide & checklist

The previous decision by NICA may have been contained to Northern Ireland. But now that the Supreme Court has weighed in the decision, it’s now binding across the whole of the UK.

That being said, the impacts felt should be slightly different depending on whether employers have workers based in Northern Ireland or the remainder of the UK.

For employers in the UK, this decision means the three-month break rule is now officially gone and is no longer binding in tribunals. This will bring significant change to deduction cases across Great Britain, not just for those concerning holiday pay, but also for other unlawful deductions.

It’s worth noting, however, that any court decision will still be tempered by the ‘two-year backstop’ from the Bear Scotland decision ruling. It means any deduction claims are limited to two years’ worth of losses, dating back from when the claimant decides to present their case. The benefit for employers is that this gives them a much clearer idea as to the extent of any possible liability, that is if payout is required (in other words, the employee(s) wins their case).

For Northern Ireland, there is no ‘two-year backstop’ and therefore will be more deeply felt by employers with Irish based workers. While it was pretty clear from the NICA decision that the three-month break rule wasn’t valid, some employers may have been waiting to see whether the Supreme Court would support or overturn this. With this final decision now set in stone, employers have all the clarity they need to rectify underpayments for employees, whether from the past or going forward.

If you provide overtime, commission or allowance payments as an employer, it might be a good idea to review your holiday pay calculations, to ensure all relevant elements are factored in on top of basic salary. It’s also worth checking if there are any other missing payments skewing calculations that could potentially lead to a ‘series’ of underpayments.

You’ll also want to roll back the clock and revisit how holiday pay has been calculated historically at your organisation. Just because you’re doing things correctly now, doesn’t mean that’s always been the case, especially if you’ve taken over a legacy system from a predecessor. That way you can spot any deductions which may now be deemed unlawful and lead to any significant liabilities that should be accounted for.

Finally, you’ll want to ensure any corrections are made promptly. Like with anything in payroll, the sooner you’re able to correct a mistake, the better the outcome. Employees have up to three months from their last deduction to start a claim. That means if you’re able to correct an underpayment sooner, you’ll limit your exposure to historic miscalculation liability.

Learn what the Carer’s Leave Act means in 2026: carers’ rights, how leave works, notice rules, postponement, and policy steps for employers.

Is paternity leave 14 working days in the UK in 2026? Learn how long paternity leave lasts, who is eligible, how pay works and what notice is required.

Learn what Labour’s 4-day week plans mean in 2026, plus your options now: flexible working, compressed hours, contracts, and HR actions.

What is the Alabaster ruling? Learn how pay rises during maternity leave affect Statutory Maternity Pay (SMP) and how to calculate arrears correctly.

A guide for employers on the Neonatal Care Act, in force since April 2025. Learn about leave entitlement, pay eligibility, notice periods & the two-tier system.

A new flexible working law came into effect in 2024. Employees have more say over how & when they work. Understand what it means for you as an employer.

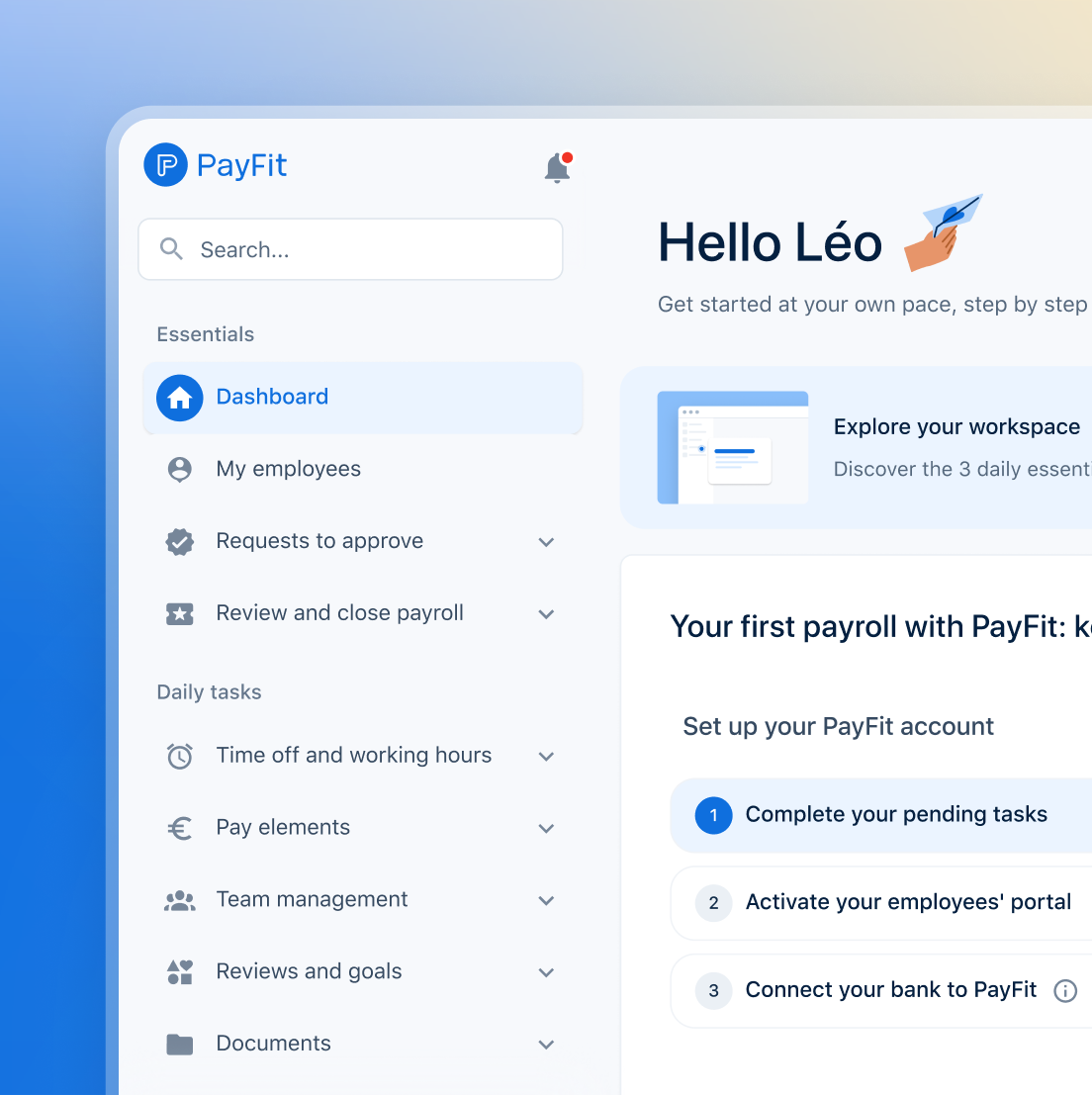

See what's new in PayFit

New features to save you time and give you back control. Watch now to see what's possible