✨ Health insurance, now in PayFit - learn more

💷 All the rates & thresholds you need to know for 25/26...right here

✨ The Payroll Journey: Start, Scale & Succeed Globally - learn more

✨ Health insurance, now in PayFit - learn more

💷 All the rates & thresholds you need to know for 25/26...right here

✨ The Payroll Journey: Start, Scale & Succeed Globally - learn more

Just over three months ago, a monumental ruling by the Supreme Court left the gig economy facing possibly its biggest challenge to date.

Yes, it may have been fairly easy to miss amid the backdrop of COVID-19 news, but, back in February, it was ruled that Uber drivers needed to be treated as workers rather than be considered self-employed.

Although the decision was made a little over three months ago, the events leading up to February's decision can be traced back over an almost five-year period.

In 2016, two Uber drivers, James Farrar and Yaseen Aslam, took Uber to an employment tribunal arguing that they were in fact working for Uber.

However, the taxi-hailing company argued that their drivers were self-employed and that, as a result, Uber was not responsible for paying any minimum wage or holiday pay.

In this article, we tackle the subject of employment status, why the ruling was made in favour of Uber drivers, what its impact will be and how companies can avoid problems in the future.

Employment status is a complex topic that a lot of employers struggle to understand and manage properly.

The UK is generally seen to have some of the most complicated employment laws, particularly in relation to employment status.

Within UK employment law, there are three primary categories of employment status.

Employees under a contract of employment who hold full employment rights

Self-employed—e.g. independent contractors

Workers who sit between employment and self-employment

While the three listed above are the primary examples, there are also other types of status—e.g. directors, partners and members of limited liability partnerships (LLPs).

It is worth noting that the categories themselves don't determine employment status. Instead, that is dependent on the terms outlined in a contract and how the working arrangements are implemented.

Someone's status affects their rights and benefits. For example, employees and workers are entitled to core statutory benefits provided to them by their employers—e.g. National Minimum/National Living Wage, paid annual leave and automatic enrolment to a pension scheme.

National Minimum Wage (NMW)/National Living Wage (NLW)

A written statement outlining the terms and conditions on the day a contract begins

Payslips

Working time rights—e.g. the right to rests and a maximum working week

Paid annual leave

Automatic enrolment to a pension scheme

Support during a disciplinary or grievance hearing

Protection for any discrimination and/or mistreatment following whistleblowing

Protection from unlawful deduction from remuneration

Health and safety protection

Employees hold further rights such as protection against unfair dismissal, minimum statutory redundancy payment as well as minimum statutory notice.

Protection against unfair dismissal

A statutory redundancy payment after two years' service

Minimum statutory notice

Statutory maternity, paternity, adoption, and shared parental leave and pay, and statutory sick pay

TUPE protection (provided TUPE applies to the transfer of undertakings concerned)

Request flexible working

Paid time off for trade union duties and ante-natal care, and unpaid time off to deal with emergencies for a dependant

Self-employed contractors have none of the rights mentioned above except health and safety protection and protection from any form of discrimination.

It is this last point that has proved so contentious concerning Uber and its drivers.

Uber drivers were, up until February of this year, determined to be self-employed contractors. Consequently, Uber drivers were previously denied the same rights afforded to both employees and workers.

The argument put forward by Farrar and Aslam was that the level of control Uber held in the working relationship tipped the balance of power disproportionately in Uber's favour.

The Supreme Court agreed, and the decision stipulated that drivers were to be classified as workers and not self-employed.

Consequently, Uber drivers became eligible for significantly more employment rights than had been previously afforded to them.

The ruling was made based on the true test of employment status outlined within the Employment Rights Act 1996.

The Act reviews both the conditions and the contract of work between the individual and the company and, although the list of "tests" is long, the Uber ruling focused primarily on Uber's ability to regulate driver's working times and conditions.

Previously, Uber did do all of the following:

set and regulate the fare for a journey without drivers providing their input;

outline the contract terms for the agreement between themselves and the driver;

penalise drivers for rejecting journeys or not being active on the app;

and terminate a driver's profile on the app should their rating have fallen below a certain level.

These conditions amounted to Uber having too much influence over the terms of a driver's self-employment and meant that drivers were essentially at the mercy of Uber and the decisions that they took. For example, the only way a driver could increase their earnings was by working longer hours, similar to what would be required if the drivers were employees.

Uber argued that it was strictly a booking agent that hired self-employed drivers to complete their customers’ journeys.

By identifying as a booking agent, Uber was able to avoid paying 20% VAT on fares.

The ruling is a significant one for Uber, and it means that there is a chance that they will need to backdate entitlements — e.g. NMW and annual leave — to the drivers who initially brought the employment status claim to a tribunal.

However, for the gig economy as a whole, the impact may be even more far-reaching.

There are approximately five million people currently working in the gig economy, and the ruling now sets a precedent for how they are treated in the future.

The Supreme Court's decision is important because it centres on the idea that if companies are going to control the working arrangements of their self-employed contractors, then by default, they will also need to absorb responsibilities for their working conditions and general wellbeing.

Essentially, the power has been removed from companies such as Uber and has been given back to the drivers.

Consequently, companies will likely have to spend more time and attention on the contracts and working arrangements provided to self-employed contractors.

The determination of employment status is now seen as a core part of HR and payroll processes.

Previously overlooked, employment status has been put under the magnifying glass and organisations are taking great care to ensure that they correctly determine statuses before any work is undertaken or workers become engaged.

However, another important point is worth considering: what if the workers want to remain self-employed?

For many workers, the gig economy, and the associated self-employment status, is a positive thing. Perks such as having the capacity to undertake different assignments, develop new skill sets and set more flexible hours are highly valued.

The downside to the Uber ruling for workers is that if they are determined to be workers, they cannot opt out or remain self-employed. Furthermore, the control over their tax position is now determined by the company they undertake work for.

However, on the flip side, companies that wish to retain their current self-employment arrangements with those who undertake work for them may have to relinquish some of the control they have previously had or risk being in the same position as Uber.

Several measures can be taken for companies keen to avoid a similar situation to the one Uber found themselves in.

For instance, companies should take time to assess and consider someone's employment status before the contract begins.

This would help avoid ambiguity and prevent employers from leaving themselves exposed to litigation further down the line.

As this is influenced significantly by the working conditions set out within the contract, employers need to think about what their contract says and where the control within the working relationship lies.

Things that can impact the employment status of a person undertaking work can include, but is certainly not limited to:

who provides the equipment for the individual to complete work;

whether or not the worker can send a replacement to do work on their behalf;

who decides when and how often the individual works;

who is responsible for recuperating any financial losses as a result of work undertaken.

Equally, when a person's employment status has been determined, companies must ensure that the minimum entitlement of employment rights are offered to each type of worker.

Once this has been done, companies should also take the time to regularly review contracts and the arrangements between themselves and an individual to ensure that nothing has changed that could impact their employment status.

Although this may be a costly endeavour, it is likely to be cheaper than facing the prospect of legal action or having to backdate payments for people who may have been allocated the wrong employment status.

Once this has been done, companies should also take the time to regularly review contracts and the arrangements between themselves and an individual to ensure that nothing has changed that could impact their employment status.

Although this may be a costly endeavour, it is likely to be cheaper than facing the prospect of legal action or having to backdate payments for people who may have been allocated the wrong employment status.

Learn how to register for Payrolling Benefits in Kind (PBiK) & simplify HMRC reporting. Discover 2025/26 updates & prepare for mandatory payrolling in 2027.

We explore the proposal for a £1,600 monthly universal basic income (UBI) trial in England, considering all the pros, cons and payroll implications.

If you pay Class 1 National Insurance, you can qualify for what’s called the Employment Allowance, and a lower Employer NI bill. Find out how here.

The 2024 Autumn Budget has landed. What does the new Labour government have in store for businesses and their employees? We recap the top announcements made.

Read our guide to answer the question ‘what is small employers’ relief’, to find out how you can qualify as a business, and how much you can claim.

In this post, we’ll look at TUPE (Transfer of Undertakings Protection of Employment Rights), how it works and what employers need to know.

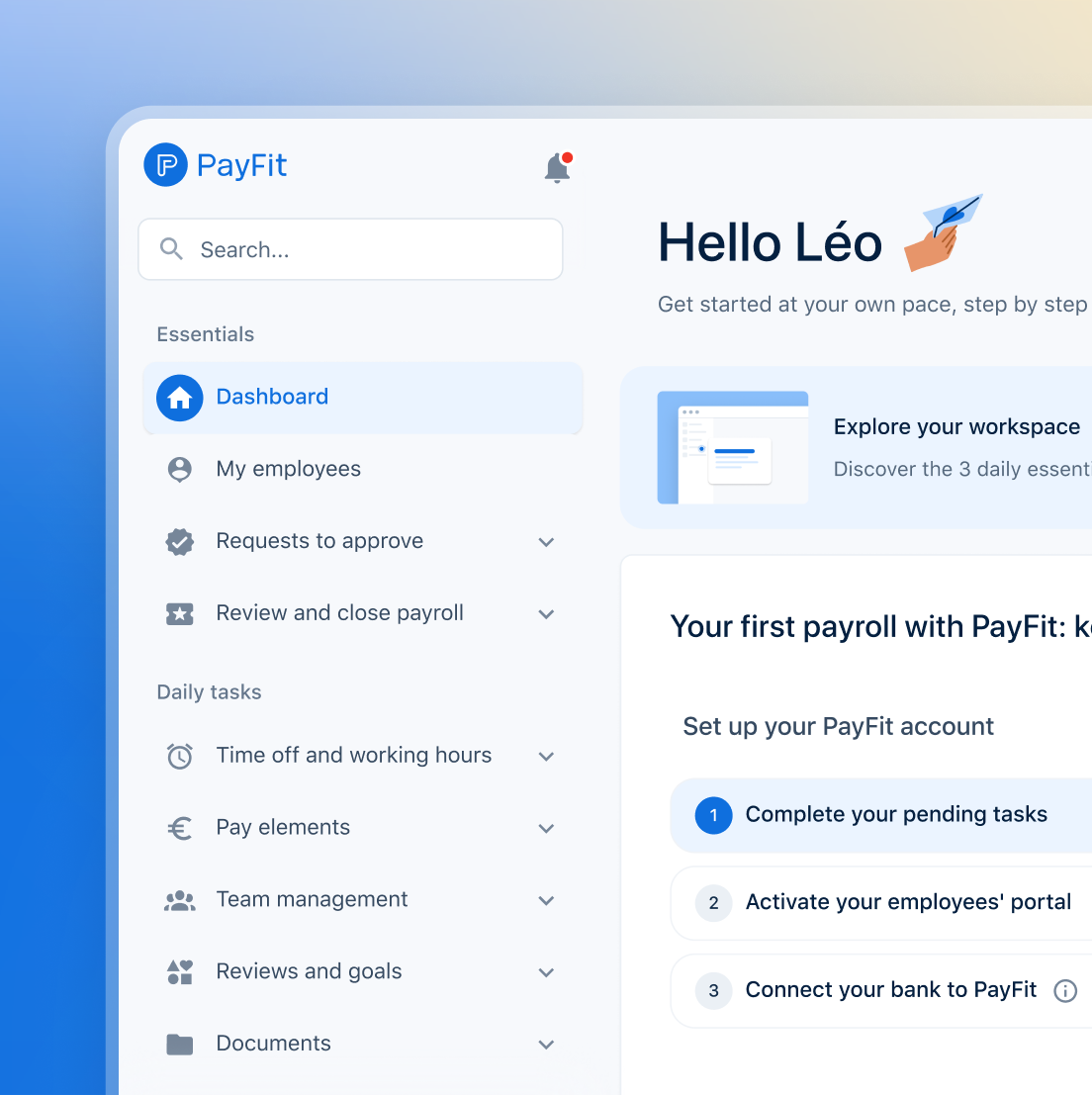

See what's new in PayFit

New features to save you time and give you back control. Watch now to see what's possible